Naloxone Access

Published Feb. 14, 2022

Download PDF

Key Points

- Naloxone is a life-saving opioid antagonist that can reverse an opioid overdose. Tennessee law makes it available to anyone with or without a prescription and protects from civil suit any physician who prescribes it, and any bystander who administers it to those who they believe are experiencing an overdose.

- The vast majority of all naloxone is distributed by the Regional Opioid Prevention Specialists (ROPS). ROPS provides naloxone to the public directly, as well as to first responders, anti-drug coalitions, and other points of contact with the substance use population. Syringe service programs (SSPs) are permitted to operate in the state of Tennessee as of 2018, with distribution of naloxone among their primary responsibilities. SSPs also obtain some of their naloxone from ROPS.

- Production delays, among other factors, have led to a nationwide shortage of naloxone. This has increased the urgency of improving naloxone distribution policies.

What is Naloxone?

Naloxone is not an opioid, nor is it similar to an opioid. It is an opioid antagonist, meaning that it binds to opioid receptors in the nervous system, blocking them from working. It can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose and prevent a patient from feeling the euphoria of getting high. It only works for opioids. It cannot prevent or reverse a methamphetamine or alcohol overdose, for example.

Naloxone can be administered in different ways. It can be injected intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously. This requires a syringe. It is also inexpensive, and for this reason is favored by Emergency Departments, SSPs and by people who inject drugs (PWID). However, some people in recovery can find the needles to be triggering and bystanders trying to reverse an overdose are often intimidated by having to use a needle.

Naloxone is also available as a nasal spray, sold under the name Narcan. This is the most well-known variety of naloxone and is preferred by both bystanders and many people who previously injected drugs. It is very easy to use, but it is much more expensive. A naloxone nasal spray called Kloxxado that is double the dose of Narcan has recently become available as well.

There is also a drug known as naltrexone, trade name Vivitrol. Like naloxone, it is an opioid antagonist, but unlike naloxone, it can treat alcohol use disorder as well as opioid use disorder. Crucially, it is used to prevent euphoria only after the subject is no longer under the effect of the drug and withdrawals have ceased. It is not used to reverse an overdose. Such reversal is naloxone’s primary function.

Ongoing Research and DevelopmentResearch is currently being conducted to develop transdermal naloxone patches with reservoirs that would remain active for up to 48 hours. Naloxone does not stay in the body as long as opioids, which means that one overdose can require multiple doses of naloxone (either intranasal or intramuscular) to treat. With a long-acting patch, this would make addressing overdoses even more safe and efficient. |

Current Naloxone Distribution Policies

Tennessee’s Good Samaritan Law, passed in 2014, protects healthcare providers from civil suit when prescribing naloxone to a person at risk of experiencing an opioid overdose or a family member or friend in a position to assist a person at risk of an overdose. Furthermore, anyone administering naloxone to someone they reasonably believe is experiencing an overdose is also protected from litigation under this law.

Pharmacies are a principal location for the average person to acquire naloxone. Pharmacists are permitted to dispense naloxone on a standing order, and naloxone is covered by insurance, including TennCare. Furthermore, Tenn. Code Ann. § 63-1-157 passed in 2016, allows pharmacists to dispense naloxone to anyone at risk of an opioid overdose, or to a family member, friend, or close associate of such individuals without a prescription and with “Good Samaritan” legal protection, provided the pharmacist receives training from the Department of Health.

Barriers to Pharmacy DistributionMany large pharmacy chains such as Publix, Walmart, CVS and others may have corporate policies that conflict with this privilege, leading to a mismatch between what is allowed at the legislative level in Tennessee and what is permitted at the company level. In other words, even though the state permits a pharmacist to distribute naloxone to an individual that they determine may be in need, their company might require additional verification or stipulations (such as requiring a referral from a clinician or a health department) that make this more difficult for the patient than the collaborative practice agreement permits. Additionally, many pharmacies only carry Narcan or Kloxxado, and not the much less expensive IM naloxone, which limits the choice to the patient. Furthermore, some pharmacies are hesitant to stock naloxone at all. |

In 2018, Public Chapter 413 was signed into law, legalizing syringe service programs (SSPs). SSPs, which operate from a harm reduction paradigm, are nonprofits certified by the Department of Health to provide numerous services to reduce overdose deaths and the spread of transmissible diseases such as hepatitis and HIV. They do this by providing education and making referrals to mental and behavioral health services, distributing unused and properly disposing of used injection supplies, and—crucially—by dispensing naloxone.

Choice Health Network, a Knoxville-based SSP, distributed 23,706 doses of Narcan and injectable naloxone in 2019 alone. Three of the ten SSPs operating across 7 counties currently listed on the State’s website are in fixed locations; the rest are mobile. Live Free Claiborne, the State’s tenth SSP, only just opened in the spring of 2021.

Regional Overdose Prevention Specialists (ROPS)

Regional Overdose Prevention Specialists (ROPS) serve as major points of contact for the distribution of naloxone in Tennessee. They also provide training and education on overdose response and prevention to clinicians, officials, and the general public. The state is currently divided into 13 regions, with over 20 specialists divided among each region. All 95 counties are represented.

Between 2017-2021, ROPS distributed more than 206,000 doses of naloxone, saving at least 26,000 lives (and likely more, considering that stigma can lead to underreporting of drug-related data). They have provided free training to the public, teaching at least 200,000 individuals how to administer naloxone in all of its forms, as well as the chemistry of addiction, strategies of overdose prevention, identification and response, and how to overcome stigma and compassion fatigue. The vast majority of all the state’s naloxone that is acquired by SSPs, first responders, anti-drug coalitions, and other primary points of contact flows through ROPS.

Production Shortages Inhibit Access

It is also important to note that since it was approved by the FDA in 1971, the price of naloxone has steadily increased, particularly so over the last decade when demand for the drug skyrocketed in response to the opioid epidemic. Injectable naloxone now costs about $30-45 per vial, while nasal spray varieties like Narcan cost over $130 per box on average. Each box of Narcan contains two doses.

Unfortunately, there is currently a national shortage of injectable naloxone, which is the least expensive variety. Pfizer, who manufactures injectable naloxone, halted production in April 2021 and reports that they will be able to resume production in February 2022, but the shortage may extend for some months after that date. The Opioid Safety and Naloxone Network Buyer’s Club, a coalition of harm-reduction programs across the country that has a distribution deal with Pfizer, estimates that this 250,000 dose backorder could lead to an additional 12,000-18,000 overdose deaths this year. Pfizer states that the shortage is unrelated to the production of its COVID-19 vaccine but rather due to manufacturing issues, and that they are working with the FDA to improve the situation. Narcan and other nasal sprays are not currently backordered, but as they are much more expensive than injectable naloxone, this can exacerbate budgetary constraints for primary distribution centers. This shortage has increased pressure on policymakers and healthcare services to carefully prioritize the distribution of naloxone doses.

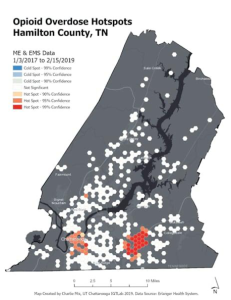

Distribution InnovationResearch is being conducted to identify strategies to improve distribution practices by targeting areas with the highest need for naloxone. Researchers at the Interdisciplinary Geospatial Technology Lab (IGTLab) at UT Chattanooga utilized two years of EMS data and spatial analysis software to develop maps of overdose hotspots, which could then be used to more accurately apportion doses of naloxone to nearby facilities. This mapping technology can lead to more strategic distribution of naloxone to areas with greater need, ensuring that limited doses do not go unused.

|

Naloxone Distribution: Best Practices

- When there is not a production shortage, IM naloxone is a significantly more cost-effective variety than the nasal sprays. With IM naloxone costing $30-40 per single dose vial and the nasal sprays $130 per box (2 doses), an individual can purchase twice the doses by buying the IM version. Furthermore, harm reduction organizations such as SSPs can obtain IM naloxone for as little as $1 per vial or for free.

- There is concern that the IM syringes will be used by people to inject drugs intravenously, but the needle gauges and lengths used for IM injection are fundamentally different from needles for intravenous injections and cannot be used to inject drugs.

- Pharmacists are legally permitted to distribute naloxone to a person they deem is in need, provided they attend a training session from the Tennessee Department of Health. However, many may not be aware that such training is online and publicly available for free. Anyone interested in naloxone training may view this video. QR codes linked to this video should be made and distributed.

- Organizations that serve people with substance use disorder should be aware of pharmacies that have naloxone policies in line with the Tennessee collaborative practice agreement, so that people can be made aware of locations where they might easily obtain the overdose-reversing medication.

- Health departments could operate as an additional point of contact for the general public to obtain naloxone. Currently, Tennessee Health Departments do not distribute naloxone to patients. Instead, a patient seeking the overdose-reversing medicine may be referred to an SSP, ROPS, or pharmacy. Because some health departments serve many people with substance use disorder through their CDC-funded harm reduction programs, they may be able to function as an efficient point of distribution for naloxone

- Distributors should practice caution with ordering naloxone in bulk. Bulk ordering is appropriate to fulfill a need or a supply gap. However, spending remaining grant money to meet deadlines might lead to shortages elsewhere. Distributors should work to encourage carryover procedures for distribution programs so as to avoid generating artificial shortages in the supply chain.

- Many individuals with opioid use disorder are involved in the criminal justice system. Incarcerated individuals often experience a reduction in tolerance upon discharge from jail, meaning that they could accidentally overdose if they then attempt to return to their prior normal doses.

- This is a well-documented problem. A study in Washington State found that individuals recently released from prison were 129 times more likely to suffer a fatal overdose than the general population. In North Carolina the formerly incarcerated had 40 times the risk of suffering a fatal opioid overdose within 2 weeks of release. Naloxone could be made available upon discharge from jail. Such efforts are already underway in multiple New York state penitentiaries.

- This could likewise be standard procedure when discharging patients from Emergency Departments following opioid overdose. Most opioid overdoses are accidental; most people using opioids therefore would benefit from having improved access to naloxone in order to prevent deaths.

- This is still an active area for research. The evidence for efficacy in reducing overdoses at this point is mixed. Nevertheless, the ED represents a window of opportunity for harm reduction practices and could be effective especially if paired with initiating treatment of medications to treat opioid use disorder upon discharge.

Policy Brief Authors:

Jeremy Kourvelas, UTK, MPH Student

Jennifer Tourville, DNP, UT System, Director of Substance Misuse Outreach and Initiatives

William Lyons, PhD, UTK Howard H. Baker Jr. Center for Public Policy, Director of Policy Partnerships

Secondary Authors:

The SMART Policy Network Steering Committee